Information Technology Services (ITS)

When the power failed…

The day after a power failure on April 4, 2019, which affected almost all buildings on the University of Toronto’s St. George campus, John Calvin, Data Centre Manager in the Hardware Infrastructure Group in EIS, wrote the following account of his thoughts and observations to share what went into keeping the ITS Administrative Data Centre (aka DCB) up and running throughout the power failure. It is an account aimed at those of us who, like John, are interested in the technical minutia and can appreciate the careful thought and hard work that goes into preparing for such events.

– Patrick Hopewell, Director, EIS

There was a power failure at Toronto Hydro’s Cecil Street Transmission Station on Thursday, April 4, 2019 that left most buildings on U of T’s St. George Campus without power.

The event began at 6:59 p.m. and lasted nearly 90 minutes. For many on campus, this was a terrible inconvenience. Many buildings had to be evacuated, the U of T Police telephones lit up like a Christmas tree, and thousands of people had their events cancelled. It could have been much worse and it could have lasted much longer.

But power failures are a fact of life that we all experience. Whether it is a blown fuse or tripped circuit breaker in your home or a downed electrical pole on your street, the effect is the same: sudden darkness and an eerie silence followed by the questions, “How widespread is the outage?” and “How long will it last?” Looking out your windows will usually answer the former, but the latter is often unanswerable before power has actually been restored.

The ice storm in December 2013 left many without power for three or more days, but base building power to the ITS Data Center was never lost in that event. In the blackout of August 2003, before the re-designed data centre facility existed, everything in the machine room lost power almost immediately and most systems were on a UPS with dead or aging batteries. There wasn’t time to shut systems down gracefully.

Being on Toronto Hydro’s Cecil Street Transmission Station was a benefit, then as now, because it in turn feeds the hospitals and is always prioritized during efforts to restore power to the downtown core. U of T was among the first Toronto Hydro customers to have power restored in 2003.

During this past event on April 4, Data Centre staff immediately started receiving automated alerts that something was wrong. The first message that I received read “Base building power has been lost.” That is enough to raise the hair on the back of one’s neck and to quicken the pulse. The second message was “Generator ON”, which was reassuring, but there was still a lot that could have gone wrong in the six seconds between “Base Building Power has been lost” and “Generator ON.” Everything after the first message has to work flawlessly to avoid calamity.

At 7:02 p.m., I called my manager, Tom Molnar, and we talked for two minutes. Very quickly, requests went out via SMS text messages and telephone calls to everyone in the Hardware Infrastructure Group (HIG) to perform sanity checks on all systems and report status. A Microsoft Teams ‘Incident Response’ channel was used to coordinate with other staff members in EIS and beyond.

The first sanity check for me was this: “Can I reach the Data Center monitoring tools from my PC at home?” I could reach them, so the facility must have stayed up.

There were two remaining questions to which I needed immediate answers: was I looking at an instrumentation problem or was there really a power failure? If it was a power failure, was it the whole building or just our facility? The distinction may seem moot to most, but that determined who got alerted next. The fact that the first two alerts made it to me suggested that others who should have received them also, probably did.

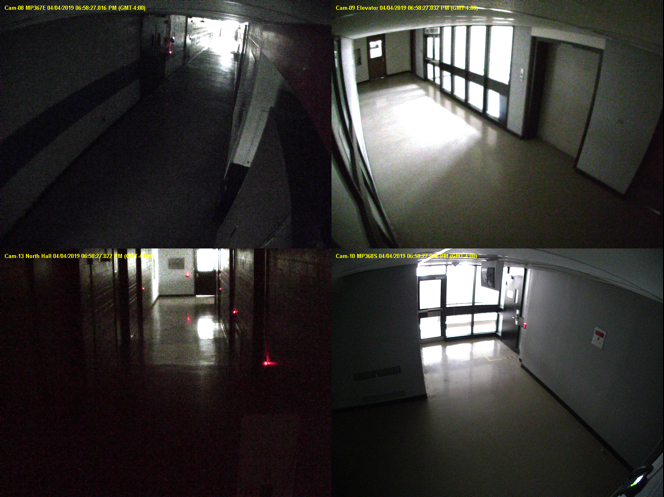

Checking our surveillance system first, I reached this conclusion: whatever was happening, it also killed the building lights, and the emergency lighting in the hallways and stairwells had not come on. They would come on later as we discovered. Aside from the red glow of some FOB readers, the only light in the hallways was daylight and that was going to fade in about an hour.

At 7:04 p.m., I received a text from Patrick Hopewell, my director. I replied telling him that the power in the building was in fact off and that we were running on the generator. He and Joseph Caprara, a member of the data centre operations team, happened to be close to the campus and quickly made their way to the Data Centre, passing by many university buildings being evacuated due to lack of power.

Having notified Patrick and Tom, the two people who needed to know, I had to focus on my part of the response until I had more information to report. My highest priority was to answer this question: “How deep is the trouble we’re in right now?”

Computers don’t like losing power, but they also don’t like it when they get too hot either. If they’d lost power, there’d have been nothing to be done but to pick up the pieces later. But they were all still running and it wouldn’t take long for them to overheat without the pumps moving chilled water through the cooling plant and the air-handlers circulating the air through the cabinets.

While the loss of power, before a graceful shutdown can occur, may lead to database and file-system corruption, it is the subsequent and normally abrupt restoration of power that is most often responsible for any actual damage that may result to electrical and mechanical infrastructure components.

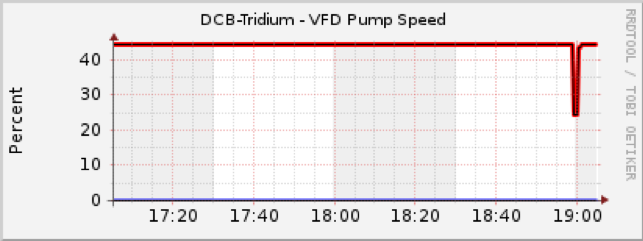

We graph almost everything about the facility and at a glance I can see if something is amiss. To find out if the pumps are running and see what actually happened, the graphs are the quickest way to check. The graphs included below display the past two hours, by default. The cooling pumps are redundant, alternating weekly to wear evenly. The air handlers in the Data Centre are on the UPS and they keep the air moving through the facility, so as long as one pump recovers, we have minutes, rather than seconds, to respond to any more issues that may arise.

The red line at the top shows that pump #1 was running at 45% after the event and the blue line at the bottom of the graph shows that pump #2 was not running. That was as expected. The dip in the red line at 18:59 (6:59 p.m.) wasn’t normal, so that told me we did take a power hit just before 7 p.m. and that the pumps had recovered. The chilled water loop stopped only for about 15 seconds. With the residual heat-carrying capacity of the circulating chilled water, we had a few minutes to look for other potential problems.

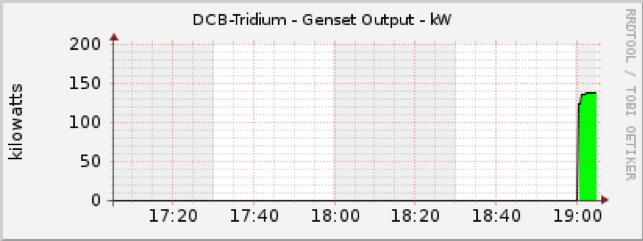

The next thing I needed to know was how the generator was doing. If everything was running properly, we should have been drawing about 135 kilowatts (kW). It was only 6°C outside, so it didn’t take much energy to cool the place. It takes much more power to keep the place cool on the hottest day of the summer.

That graph told me that we were seeing the right amount of power draw on the generator to run all of the equipment in the Data Centre. Two messages in the flurry at 7:03 p.m. said this: “Informational – UPS: Batteries are charging or resting.” These told me that the power coming from the generator was within the UPS tolerance and we were no longer depleting the batteries on either UPS.

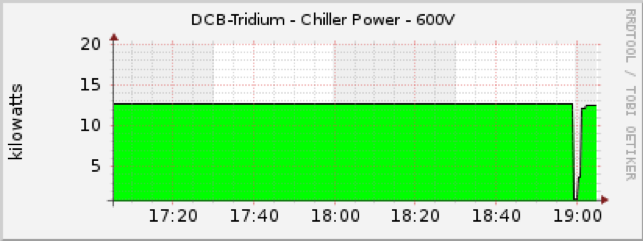

With that ticking clock reset, and holding at 60 minutes, the next question was, “How happy is the rest of the cooling plant?” When the chiller loses power, it reboots as power is restored. Some things don’t reboot gracefully if this happens too quickly or too often.

So, the chiller was drawing the same amount of power from the generator that it had been from Toronto Hydro before the event began. That was a relief and meant that, whatever remaining ticking clocks there might be, we had hours remaining to act, not minutes. As long as we didn’t run out of diesel fuel, we’d probably be alright.

At 135kW combined IT and mechanical loads, the generator consumes about 16 US gallons of fuel per hour. Since our monthly generator test was only three days earlier, I knew that on Monday the day-tank had been topped-up and contained more than 8 hours of fuel and that the main tank, below grade, had more than 24 hours. We certainly had enough fuel to wait until morning for a fuel delivery.

When both the day-tank and the main tank are full, and one of the redundant fuel pumps is working, we could last (at 135kW) almost two days before we had to have a diesel delivery. It’s a different story as the facility grows and the outside temperature rises. At our end state facility load, we’d have about 18 hours of onsite fuel. That would mean a delivery every 12 hours would be needed to keep us running indefinitely.

It didn’t take the rest of the HIG team much longer than it took me to reach this point to confirm that all IT services in the facility were unaffected and running normally. We all breathed a sigh of relief.

Patrick and Joseph arrived on site at 7:23 p.m. and while Joseph repeated his usual twice daily visual inspection of all IT equipment in the Data Centre, for a third time that day, Patrick managed communications, both internal and external, from his office. A conference call among the ITS directors and the CIO was quickly convened.

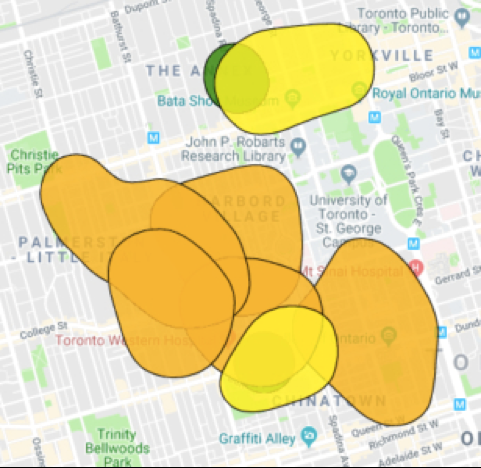

Patrick posted to the ITS System Status page at 7:36 p.m., once the entire HIG team had provided their status assessments, reporting that “The primary administrative data centre continues to run on emergency backup power and central services hosted in the data centre appear to be operating normally” and providing an update at 7:41 p.m. and 8:16 p.m., which included a link to Toronto Hydro’s outage map.

Tom Molnar had arrived just before 8 p.m., having been coordinating the HIG response while on his way in. Patrick remained onsite until the power was restored and confirmed that the facility was operating normally afterward.

Since our facility was commissioned in 2012, we’ve never had an unplanned power failure. We’ve been meticulous in our attention to maintenance and testing of the standby power systems. We added a second UPS and secondary upstream electrical distribution system in 2017 and completed the five-year major maintenance on the generator in October 2018. Our annual maintenance on the fuel system was completed at the beginning of February, during which the fuel was scrubbed with 2 micron filters to remove any particulate matter.

When I say we, I include the teams from Enterprise Infrastructure Solutions, Facilities & Services, Cummins Power Generation and Ehvert Mission Critical. All have been well-represented and have participated in every power-fail test. It isn’t a real test if you don’t turn the power off and let the chips fall where they may. There are always risks when you do that, so everyone has to know what could go wrong and be prepared with a back-out plan.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that, from the first meeting on April 16, 2010 of the Project Planning Committee for the U of T St. George Campus Data Centre Renewal, the issue of an inevitable and prolonged power failure was top of mind, and we planned for it with a backup generator and Automatic Transfer Switch (ATS).

Since the first piece of production hardware was installed, we have intentionally killed the power to the facility monthly while a team of subject matter experts monitors every aspect of facility operations, from the ATS transfer to generator when the power is cut through the ATS transfer back to normal power and the resumption of normal operation.

We have performed this procedure 75 times since commissioning the data centre, just so that yesterday’s event, or one much like it, wouldn’t cause the nightmare yard-sale that it could have been. Three weeks of putting Humpty Dumpty back together again could have completely undermined our academic mission during exam week, not to mention our fiscal year-end. When you calculate those costs, the generator likely paid for itself in our first inevitable 90-minute unplanned power event.